Brazil’s Soul, in Form of a Stadium

RIO DE JANEIRO — Generations of Brazilians have grown up in the Estádio Jornalista Mário Filho, known around the world as the Maracanã. Built for the 1950 World Cup and at the time the largest stadium in the world, it became an instant national landmark, a symbol of Brazil’s soccer-centric culture.

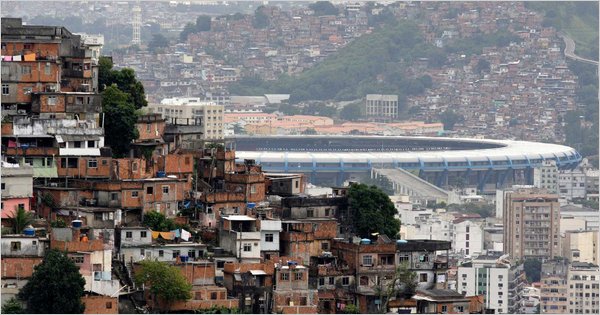

The stadium, which is likely to host the 2014 World Cup opener and final, is flanked by hills and favelas, the city’s notoriously poor slums. Far above, from behind the iconic statue of Christ the Redeemer, the distant Maracanã looks like a still birdbath amid the pulsing metropolis.

Not anymore.

That general admission area known as the geral has steadily disappeared. The stadium’s official capacity of 173,000 was more than halved during preparations for the 1999 FIFA Club World Cup, when the Maracanã was converted to an all-seater, in which every patron has a seat. For the 2007 Pan American Games, the general admission area was closed off, as is the entire stadium today. Its capacity — some say more than 200,000 crammed in for the 1950 final, a heartbreaking loss to Uruguay — will be just 76,525 when the renovated Maracanã reopens in 2013 to host the Confederations Cup, the World Cup’s dress rehearsal. Those renovations will cost more than $600 million, according to the state’s Office of Public Works, but they were not entirely welcomed.

“It’s just one reform after another without anyone ever doing any kind of research as to what the people who actually use the stadium want,” said Christopher Gaffney, a visiting professor of urbanism at the Federal University in Fluminense in the state of Rio de Janeiro.

Gaffney is part of a recently formed group of activists called the National Fans’ Association, which is seeking a greater voice in the future of soccer in Brazil. The culture and the history of Brazilian fandom is being swept away, they argue, as stadiums are modernized. At the heart of this transformation, Gaffney says, is commercialization.

“The culture of Brazilian football isn’t just one of going to the game and having a hot dog and a beer,” he said. “It’s active participation in what is a fundamental element of Rio’s culture.”

At another Rio stadium, the Engenhão, large bamboo poles wave 10-foot-tall flags just inches over the heads of fans in the section of seats behind the goal. Drums are beaten, songs are sung and fans run up and down the stairs of the stadium, which was built for the Pan American Games. These are the cheap seats, but at $18 they are 10 times as expensive as the former standing area at the Maracanã. At a recent match between two local teams, half the stadium was empty.

As more and more Cariocas are effectively priced out of attending matches, an increasing number of people have joined the effort of the National Fans’ Association. The organization was created in October and has 2,700 members.

“They tried to tell themselves that this was not happening, that football was still the same, that supporting their club was still the same, that the stadiums were still the same,” said Marcos Alvito, founder of the group and a history professor at the Federal University in Fluminense. “It’s not true and they know it.”

Luxury boxes, modern seating and safety improvements are reasons Brazil’s stadiums are changing as the country prepares to host the World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics. They are also likely to increase ticket prices. But the Maracanã, a municipal stadium, is also one of the city’s revered public spaces. As these global changes seep into Brazil ahead of its spotlight-luring turns hosting the world’s two largest sports spectacles, the public nature of the Maracanã of the past is under threat.

“Do you give up the vitality of the Maracanã as a public space, a rare type of space in Rio where you can actually get together people of different social classes?” said Bruno Carvalho, a Rio native who is an assistant professor of Brazilian studies at Princeton. “What’s the price that you pay when you don’t allow that to happen?”

Carvalho said he was not worried that the participatory nature of Brazil’s fervent soccer fans would fade away. But he does worry about the Maracanã’s role as an egalitarian space in a heavily unequal city like Rio.

“What could be lost is the nature of the stadium experience as something that cuts across the class segregation of the city as a whole,” Carvalho said.

Brazilian officials argue that ticket prices for soccer matches remain low compared with those of many of the leagues in Europe, and that the sorts of stadium renovations that are under way are badly needed. Brazil’s stadiums today are not up to the standards of its fans, according to Rodrigo Paiva, a spokesman for the 2014 World Cup’s local organizing committee.

“The dedicated supporter cannot be treated as a second-class citizen in the local stadiums and deserves better viewing conditions, more safety, comfort, as well as access to good catering and other services,” Paiva said in an e-mail.

For the members of the National Fans’ Association, better services and modernized facilities are but a tradeoff, fulfilling the desires of the wealthy while ignoring those of the poor. They know that much of this work has to and will be done before the World Cup, but they remain hopeful that the process can be altered along the way to reflect the will of the full spectrum of Brazilian fans.

“Maybe we can make it necessary that they include cultural space, or that they have to at least consult with urban planners or neighborhood associations to see how they should integrate what will basically be white elephants into the urban context,” Gaffney said.

Though a report released recently by a government watchdog group known as the Brazilian Audit Court warned that work on the stadium was progressing too slowly, several of the World Cup’s biggest games will most likely take place inside the renovated Maracanã in 2014. Protected as a historic site, the stadium’s structure will remain largely the same concrete bowl millions of Brazilians have known. But inside, the stadium will be unavoidably — and to some, unfortunately — different.

“It’s such a part of the public memory and the very texture of the city that it’s hard to imagine it being something else,” Gaffney said. “But now it is. And people are going to have to come to terms with the fact that it is not going to be what it was.”

A version of this article appeared in print on May 6, 2011, on page B11 of the New York edition with the headline: Brazil’s Soul, in Form of a Stadium.

ORIGINAL ARTICLE:

By NATE BERG

Published: May 5, 2011

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/06/sports/soccer/06maracana.html?pagewanted=2&_r=2

A video from Al Jazeera: Football’s World Cup and the Olympic Games are pushing some of the poorest people in Brazil out of their homes. Al Jazeera investigates.