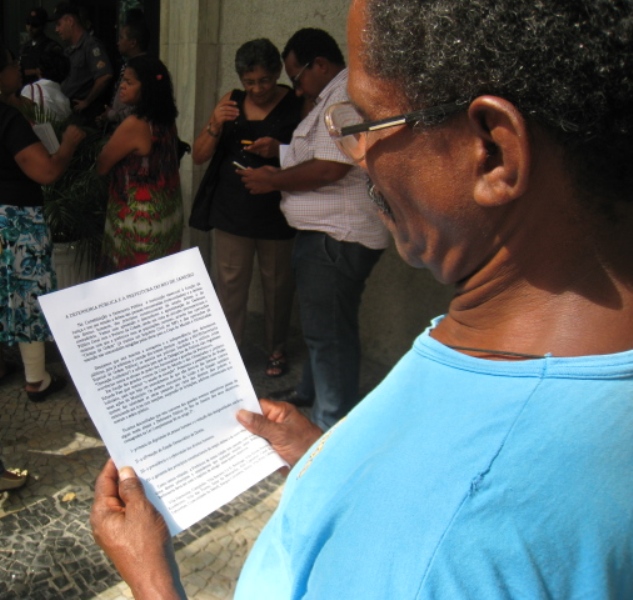

Background Information: The Pastoral das Favelas, (Pastoral Care for the Favelas), is one of several “Care” programs within Rio’s Archdiocese. There are also pastoral care programs for the elderly, disabled, street children, and disadvantaged Rio residents. The Pastoral das Favelas (PdF) is at the forefront in defending the rights of Rio’s favela residents. The PdF organizes weekly meetings at different favelas, with bi-monthly meetings hosted at arch-diocese headquarters in the Gloria sector of Rio. These meeting, held in conjunction with civil society organizations such as the Conselho Popular (Popular Counsel) and the Network of Communities and Movements Against Violence, keep city residents abreast on issues concerning government and private citizen efforts to evict favela residents. Participants take this opportunity to share information about their communities, and to better understand what is going on different areas of Rio.

Last week’s meeting: During last week’s meeting roughly 16 residents from the Borel favela were in attendance to inform that in their community of about 160 families (roughly 500 people) are facing impending eviction. This was amongst the more heavily discussed topics. Borel is a large favela in the Tijuca neighborhood of Rio, located about 20 minutes from the Rio center. Residents, lamenting the precarious conditions of their current living situations, agreed they needed to be resettled somewhere safe, and in close proximity to their previous homes. The controversy arises from frustrations at the fact that the city government has given Borel’s residents limited housing relocation options. One option is to relocate residents to the distant neighborhood of Paciência (2.5 hour bus ride from Rio city center) or to the even more remote neighborhood of Santa Cruz, which is on the outskirts of Rio, and a 3-hour bus ride from the center of Rio. Unlike Borel, which has good schools and hospitals near by, neither housing alternative has a school or hospital in proximity. Residents who went to visit these new housing units complained they are literally “located in the middle of the jungle, and that they are not even completed.”

Part of the controversy stems from the government sponsored housing program, Minha Casa, Minha Vida (MCMV). MCMV is a housing and development initiative funded by the Brazilian federal government. The program has been widely applauded because it aims to build one million housing units in its first phase. This initiative would house roughly four million Brazilians in desperate need of safe and suitable housing. In many Brazilian cities MCMV has been considered a success. In Rio de Janeiro, however, MCMV has faced harsh criticisms. This is directly related to the rapid social changes occurring in Rio. In the last several years, with the looming World Cup and Olympic preparations and falling violent crime rates, Rio de Janeiro has become increasingly expensive to live in. Real estate speculation in the city is intense, and most everywhere you look there are a variety of development projects under construction. The federal funds that were transferred to the city of Rio, and State of Rio de Janeiro, to build MCMV housing units, are being spent inappropriately by city officials on cheaper units, in remote areas of Rio de Janeiro. Few families living, working, and studying close to Rio’s city center, or South Zone, want to move hours away and live in the remote MCMV homes. The city is providing these housing units as the only option for residents being evicted from favelas. This has led many favela residents, social movements and some politicians to mockingly name the program Minha Casa Minha Remoção (My House, My Eviction). There is an increasingly troubling association between the forced evictions in Rio’s favelas and Minha Casa Minha Vida. This issue merits urgent investigation. The brunt of the problem appears to be at the state and municipal levels, where the federal funds are being quietly misused in order to save money, or perhaps for even more devious reasons which we will discuss in future blog entries. This is a blatant infringement of the law (Federal, State, Municipal) which clearly states that any person or family forced to leave their home must be resettled to a safe location, near their previous home, as not to significantly disrupt their social ties (family, school, work, family doctor, friends etc.). Increasingly MCMV is becoming the center of criticisms over the infringement of citizen rights in Rio de Janeiro, even if this topic is not yet receiving its due attention in the media.

Some experts theorize the resulting infringement on public and urban policy rights, by entities like Minha Casa Minha Vida, are directly related to housing and land speculation going on in Rio, which has shot land prices through the roof. The city often defends the remote locations of MCMV housing units by claiming there is no available space to build housing units in, or around, the city center and the South Zone. This is a transparent argument, considering new development projects are going up weekly in these same areas. The difference is that the projects under construction are mainly for private interests, whether commercial or housing. Critics rhetorically ask, “if a 600 m² or 1000 m² exists around the city center why would low cost public housing units for poor families be built when luxurious stores, offices or apartments could be built in the same locations, which would reap enormous profits for their owners and create large tax revenues for the city?” Thus the city builds the units in cheap, far removed areas of Rio for financial gains.

An equally contentious issue, related to MCMV, is that the apartments they are building are 48 m² in size. This is infuriating, considering it is clearly outlined in local legislation that in any case of forced eviction new housing must be a minimum of 52 m². While 4 square meters (43 square feet) may not seem like much, for poor families this could mean another small bathroom, storage or wash room or important space. These evictions and the MCMV building sites are disrupting the lives of tens of thousands, and have created a human rights issue of pressing concern. The reality is that with money, and the image of Brazil at stake, there is very little these community residents can do.

Another issue discussed during the Pastoral meeting was the building of the Transoeste Super Highway, located on the west side of the city. The building of Transoeste presents a series of problems, both in terms of housing rights and the environment. Dozens of medium to small favelas are being evicted and razed to make way for this large expressway, which is also traversing endangered ecosystems, such as mangroves and swamps. Unfortunately, this is one project that is almost impossible to stop, or slow down. Because of Rio’s winning bids for the World Cup and Olympics it was agreed that all infrastructural projects would have to be built, without any work stoppages, so they would be ready for the Cup and Games. This means that virtually no amount of protest could stop the building of this mega project, and the resulting human rights and environmental violations taking place, regardless of their gravity, they are being ignored. According to Rio’s Public Defender Alexande Mendes, who has worked closely for years with displaced families, these are the worst human rights violations he has seen in his career.

The next Pastoral meeting is on March 22, 2011 in the Boren favela, at 6PM. Please check back with Mundo Real for more information.